The Knockshinnoch Rescue

The following account of the Knockshinnoch Disaster is taken from the informal investigation ‘Accident at Knockshinnoch Castle Colliery Ayrshire’ by Sir Andrew Bryan, H.M Chief Inspector of Mines. The report was submitted to Parliament in March, 1951 by The Right Honourable Philip Noel Baker M.P., Minister of Fuel and Power.

Thursday 7th September 1950

- Some time after 7:30pm

Andrew Houston, overman, had collected 115 men in the neighbourhood of the inbye end of the West mine. It was apparent that the greater part of the roadways between the shafts and this point were blocked with enormous quantities of sludge and that a very long period of time, probably running into months, would be required in order to reach the mean by clearing a passage along these roads.

About 1944, in the neighbouring Bank No. 6 Mine, a district known as the Waterhead Section had been worked. Subsequently, the Main Coal in Knockshinnoch Castle had also been worked in the Waterhead Area towards Bank No. 6 leaving a barrier of coal, 200 feet between the two collieries. In order to facilitate drainage from the Knockshinnoch side, a roadway had been driven into the barrier up to a point about 24 feet from the Bank No. 6 workings. A borehole had then been put through the remaining part of the barrier to convey the water.

News of the disaster was conveyed at once to the higher officials of the Ayr and Dumfries Area of the National Coal Board, representatives of the mineworkers and the Mines Inspectorate and many were on the scene within a very short time. The position was discussed and it soon became obvious that the only hope of rescuing the imprisoned men was to make a connection through the narrow barrier between Knockshinnoch Castle and Bank No. 6. Andrew Houston, was informed of the position by telephone and he was instructed to explore the Waterhead Dook from his side. This was done and it was found that the roadways and the place containing the borehole was accessible.

The following arrangements were then made on the surface

- A Headquarters Base was established at Knockshinnoch Castle, with telephone contact between the trapped men, the Bank No. 6 office and the surface crater

- An operational base was established at Bank No. 6 which maintained contact between the underground base and the Knockshinnoch Castle HQ.

- High officials of the National Coal Board were detailed to take all practical measures to minimize inflow from the crater.

In the meantime, rescue apparatus had been made available at Knockshinnoch Castle from Kilmarnock and Auchinleck Rescue Stations and calls were sent out for all the local rescue brigade men. The Central Rescue Station at Coatbridge had also been warned to stand-by in readiness. The rescue apparatus was despatched to Bank No. 6 Mine. Volunteers were asked to stand-by to act as carriers to the rescue teams, i.e. one volunteer to carry the apparatus inbye and wait until the rescue man did his turn of duty, and then carry the apparatus to the surface again.

- 11:30 p.m.

Mr. G. Rowland, H.M. Inspector of Mines, accompanied with Mr. McParland, Manager of the Bank No. 6 Mine, the Superintendent and his assistant from Kilmarnock Rescue Station, together with two local brigades equipped with Proto apparatus and Novox Revivers, descended Bank No. 6 Mine with the instruction to make a preliminary inspection of the abandoned Main Coal workings.

Mr. A. Macdonald, Area Production Manager, had staffed the operational base at the Bank No. 6 office. The Coatbridge Rescue Station Superintendent, who had arrived with equipment and teams, was detailed to take over the responsibility of making and maintaining a rescue team rota as the men became available.

Friday 8th September 1950

- 02.30 a.m.

Mr. Macdonald and Mr. Richford, the District Inspector of Mines, descended the mine, and met Mr. Rowland and his party who were returning to report their findings. The teams had been able to travel along the old road inbye the point where the connection to Knockshinnoch Castle would have to be made. The roads were full of firedamp and the inspection had been made with the use of apparatus, a fresh-air base being established in cross-cut . As electricians, engineers and voluntary workers were now available, detailed arrangements were made on the spot for the installation of auxiliary fans in an attempt to clear the accumulation of gas.

- 04:00 a.m.

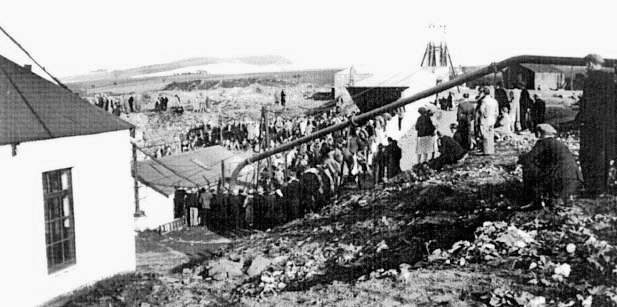

In the meantime the subsidence on the surface had increased until the area involved was approximately 2 acres in extent, and 40 to 45 feet in depth. In an attempt to prevent the moss or peat running into the pit, bales of straw and hay, trees, pit timber and hutches were thrown into the crater – to no avail. The assistance of several Fire Brigades was obtained, portable pumps were installed at strategic points around the subsidence and fresh ditches dug in order to prevent or reduce the amount of surface water flowing into the crater. Several surface drains and a burn were dammed and the water pumped to the river Afton. Messrs. Wimpey, Public Work Contractors, were called to secure the sides of the hole and take such steps to make it safe for an exploring party to enter the exposed roadway at a later time.

- Midday

By midday the gas had been cleared about 300 feet up the right-hand roadway, and hope of clearing the remaining firedamp appeared good. Rescue men were used to extend the canvas tubing from the auxiliary fan as the gas cleared, but the position fluctuated considerably and very soon it became common procedure to have to send them forward to shorten the fan tubing in order to consolidate progress.

A sound microphone obtained from the Coatbridge Rescue Station enabled telephonic communication to be maintained from the underground operational base through a normal pit phone, to the surface at Bank No. 6.

- 4.00 p.m.

The telephone to the imprisoned men began to show signs of weakening, the trapped men on the Knockshinnoch Castle side were instructed to start making a passage through the barrier which separated the two workings. They were told to halt just short of the old road lest the firedamp from Bank No. 6 should foul their atmosphere which was then reported to be free of firedamp.

- 4.00 p.m. – 9.00 p.m.

It became obvious that more urgent measures would have to be adopted if the gas from Bank No. 6 side was to be cleared in time and Fan No. 1 was replaced with one of greater capacity and Fan No. 2 was duplicated by Fan No. 3, the two to run in series. All the air available from the Bank Mine surface fan would be directed into the operational area by erection of stoppings placed at suitable points.

Stupendous efforts saw these changes in ventilation arrangements made in the course of four or five hours, but still no real progress was made. Throughout the whole period, rescue teams had been passing to and fro along the gassed-out roadway. effecting repairs, erecting a stopping , and erecting a temporary stopping inbye the point of contact with the Knockshinnoch Castle workings.

When the trapped men had received instructions to commence making a passage through the barrier, they were warned to keep a small hole in advance and to watch the direction of air. If the air came from tank into Knockshinnoch it was to be immediately plugged. Fortunately, when the hole was made the air travelled from Knockshinnoch to Bank, and so instructions were given for the hole to be enlarged to enable rescue brigade men to pass through and take food and drink to trapped men. The flow of air through the hole from Knockshinnoch to Bank did not persist, and as a precautionary measure, the hole was screened to isolate the two ventilating systems as far as practicable.

Andrew Houston, went to the holing to greet the first rescue team and conduct them to the trapped men, with food and drink. Up to this time messages from Houston to the surface had indicated that the atmosphere was free of gas in the Knockshinnoch workings. But when Houston was on his way back with the rescue team , he found men erecting a brattice at the top of the Waterhead Dook, and was informed that gas was collecting there. The trapped men had previously been told of the presence of a large body of gas in the roadway on the Bank side and of the efforts that were being made to clear it so that they could walk out, but this was the first indication of gas on the Knockshinnoch side. This news was kept back from the main body of the trapped men lest it should adversely affect their morale. Houston had to explain to them that the gas on the Bank No. 6 side had not been cleared and that it might be a considerable time yet before they could be rescued. The food and drink and the visit of the rescue team had cheered them greatly, but the news that they must still wait was a bitter disappointment.

It was now apparent to those in charge of the rescue operations that the clearing of the gas from Bank No. 6 workings presented a major problem and consideration was now given to the possibility of the trapped men having to be brought through the irrespirable zone by the means of self-contained breathing apparatus. With this possibility in view, instructions had previously been given to collect as many sets of Salvus apparatus as possible from all readily available sources. As it is intended only to be used for half an hour , it is both simpler and lighter than the Proto, which is designed for two hours use, and when fully charged it weighs only 18 lb.

Saturday 9th September 1950

- Early Morning

A scheme was formulated to use rescue teams consisting of six members, each team to escort three of the trapped men wearing Salvus apparatus, through the irrespirable zone. It was estimated that it would take forty hours to evacuate all the trapped men. It was fully realized that this was a risky venture, since the trapped men were wholly unaccustomed to wearing rescue apparatus, and the hope was that the gas filled roadways could be cleared and the men would be able to walk out in fresh air.

- 03:40 am

Soon after the holing was made between Knockshinnoch and Bank, disquieting rumours began to circulate about the state of mind of the trapped men and rumours prevailed that some were talking about a suicidal dash for safety through the gas-filled roadways.

Mr David Park, Deputy Labour Director of the Scottish Division of the National Coal Board who had arrived late on the night of Friday 8th September volunteered to join the trapped men in order to explain the position fully to them, tell them about the difficulties being encountered and all that was being done to effect their release. As a boy David Park had worked in the pits in New Cumnock and at one time had been captain of the local rescue brigade. He knew many of the imprisoned men personally, including Andrew Houston, whom he felt he could help in his efforts to control the men. He also had experience in the use of the Salvus apparatus. At 3:40 a.m. wearing the Proto apparatus he joined a rescue brigade team and entered the Knockshinnoch workings.

David Park told the men all that was being done to rescue them, calmed their fears and generally restored their morale, and thus assisted Andrew Houston to restore discipline.

After addressing the men, he had a look around and found that the atmospheric conditions were far from satisfactory. The percentage of firedamp was steadily increasing, and he instructed the captain of the rescue team to inform those in charge of the rescue operations that the condition of ventilation was quickly deteriorating and was much worse than he could intimate over the telephone in the presence of the trapped men.

It was now realized that drastic measures would have to be taken and a new scheme was drawn up forthwith. This was to form a ‘chain’ of rescue brigade men along the whole length of the gas filled roadway on the Bank side who could pass sets of Salvus apparatus through to the trapped men. A rescue team would enter the Knockshinnoch workings and instruct the men in the use of the apparatus, fit it on them, and pass them out along the ‘chain’. A general call was made for additional trained rescue brigade men from Lanarkshire to enable the scheme to be put into operation with the least possible delay. Although the proposals were not in accordance with Rescue Regulations, the principal officials on the surface agree, but with grave misgivings put the scheme into operation about midday on Saturday 9th.

- 12:30 p.m.

Five rescue teams were present at the main fresh-air base. Ample reviving apparatus, stretchers, blankets and first-aid men were available as well as two doctors with medical supplies. One of the imprisoned men was in a very weak state and a team was sent in with a stretcher, two sets of Salvus apparatus and blankets at 12:30 p.m.

- 2:45 p.m.

The sick man was brought to the fresh-air base. By this time, owing to various delays and incidents, all five teams had been used and there was a further two hours’ delay before sufficient teams could be assembled at the base to enable the main ‘chain’ operation to be attempted.

- 5:00 p.m.

The position was as follows :-

- 87 sets of Salvus apparatus, mainly from Fire Stations had been deposited at the advanced fresh-air base (with more on the way) together with 100 spare cap lamps.

- A ‘chain’ of men at intervals of a few yards extended from the advanced fresh-air base to the main base where the Doctors , with their equipment were stationed, together with 30 volunteer stretcher bearers.

- Food, water and hot tea were available at both bases.

- One rescue team was held for emergencies at the main fresh-air base. This team was not to go to the advanced fresh-air base until a fresh team from the surface arrived at the main base.

- One team was kept at the advanced fresh air base, being finally briefed on their duties so that they thoroughly understood the operation being attempted. As a fresh team arrived from the main base, the earlier team was sent in to the operational zone.

A team of permanent rescue men from Coatbridge Station was instructed to proceed direct to the Knockshinnoch Castle side, disconnect their apparatus, do all they could to build up the morale of the trapped men, and explain both the general plan of action and the use of the Salvus apparatus before fitting it to each man and sending him out. They were to remain on this job without relief if possible. The members of the team took in Salvus apparatus and spare electric cap lamps to be used in the event of the lamps of the trapped men being exhausted. This team was informed that further supplies of Salvus apparatus would be passed to them by the other resuce brigade men who would be forming the ‘chain’ through the irrespirable zone.

Immediately afterwards four other teams were sent off, also carrying Salvus apparatus and spare lamps, with instructions to pass them forward to the Coatbridge Brigade on the Knockshinnoch Castle side. They were then to establish the ‘chain’ whereby the remainder of the Salvus apparatus and spare lamps could be passed from the advanced fresh-air base through to the trapped men.

Andrew Houston, drew up a rota regulating the order in which the imprisoned men were to be taken out . He decided that the older men should go first, but as the strain of waiting began to tell on some of the younger members, many of them were allowed to go before all the older men had gone. All the resuced men were medically examined at the undergound fresh-air base before they were allowed to proceed outbye to the surface.

- 8:15 p.m.

Andrew Houston was instructed to come out, leaving David Park in charge of the remaining men. His presence was required in order to ascertain , as far as might be possible , the last known positions of the missing men.

Sunday 10th September 1950

- 12:05 a.m.

The last of the trapped men reached the advanced fresh-air base at 12.5 a.m. on Sunday 10th September, the complete operation having taken approximately eight hours. Twenty brigades had been used in the evacuation . Excluding the Coatbridge Brigade which remained inbye through the whole operation, six brigades were constantly maintained within the danger zone which extended over 880 yards, the rescue men being spaced at intervals of twenty yards or so. This arrangement gave great enouragement to the men wearing the Salvus, an apparatus to which they were unaccustomed, as they made their way outbye to the advanced fresh-air base.

When the last of the men had been rescued, David Park organized a search with a rescue brigade to make sure that no one had been left behind. He was the last man to leave. (‘The last man walked through the gas to safety on Sunday at 1:30 a.m.’ – Bill Aitken in ‘Among the Green Braes’)

When the overman, Andrew Houston reached the surface he was able to indicate to those directing operations the places where the missing men had been working, or were last seen, prior to the inrush. It was felt, that had any of the missing men escaped the inrush and taken refuge in the workings on the rise side of the No. 5 Heading, they would have been found by the exploring parties from the trapped men and would have been rescued along with them.

From a consideration of all this information, those responsible for directing the rescue operations, in consultation with representatives of all parties, came with regret, to the inescapable conclusion that if, by chance, any of the missing men had not been overwhelmed by the inrush they were bound to have reached a part of the mine which was not only too remote for rescue brigades to reach from the fresh-air base in Bank No. 6 workings, but was in any case inaccessible. In consequence, after the 116 men from the inbye end of the West Mine had been brought out safely to the fresh-air base in Bank No. 6, the decision was taken, that no more rescue brigades should be sent in through the ‘escape road’ and that efforts should now be concentrated on an attempt at further exploration by way of the ‘crater’, since the exposed end of No. 5 Heading was seen to be open. It was thought that it might just be possible to get far enough down the No. 5 Heading and find an open road to the rise off the heading which would give access to the inbye workings in which a further search could be made for the missing men.

- Evening

By the night of Sunday the 10th, two exploring parties had entered the workings and reached a point 800 feet down the No. 5 Heading. Unfortunately, heavy rain persisted and made still worse the already precarious state of the sides of the crater: masses of moss were slowly but continually closing in on the opening into the No. 5 Heading. This state of affairs, especially when one bears in mind the fact that the heading lay on a gradient of 1 in 2, that all roof supports had probably been swept out and that with the subsequent falls it was now probably 13 to 14 feet high, rendered exploration in the heading a most dangerous and difficult affair. In the meantime, exploration from the upcast shaft had shown that all roads leading inbye from it were blocked to the roof with peat, and that little or nothing could be done from this side.

Monday 11th September 1950

By Monday, 11th September, the position at the crater was such that a meeting was held of the representatives of all the parties at which the decision was made that no further work should be carried out underground from the crater until its sides and the entrance to the No. 5 Heading were properly secured.

By this time it was felt that there could be no hope of reaching or rescuing any of the 13 missing men and that there was no justification for risking loss of life among the rescuers.

Acknowledgements

| References |

| Accident at Knockshinnoch Castle Colliery Ayrshire’ by Sir Andrew Bryan, H.M Chief Inspector of Mines. The report was submitted to Parliament in March, 1951 by The Right Honourable Philip Noel Baker M.P., Minister of Fuel and Power. |

| Black Avalanche’ by Arthur and Mary Selwood |

| ‘Among the Green Braes’ by Bill Aitken |